Although artists’ livelihoods depend on their agency and capacity to create and capitalise on their social and economic assets, there’s an inevitable — and unenviable — struggle between the intrinsic motivations underpinning their art practices and the ‘small business’ expectations of a self-employed status.

Combined with arts policy’s favouring the stability of arts institutions and salaried staff above all other considerations, this baseline disjunction puts the majority of visual artists at a social and economic disadvantage - a situation only exacerbated by world shocks such as Covid.

“Getting paid should not be a daily battle. And yes, this includes every time you want that 'informal chat' to know our thoughts too.” @DeadPigeonG

The statistics make for grim reading. Artists’ incomes moulder well below poverty level when compared with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s minimums. The success rate for visual artist applicants to Arts Council England’s Developing Your Creative Practice scheme – the national body’s one and only R&D funding source for individuals – is desperately poor.

“Painful scarcity of funding and opportunities means that we’re all in a Hunger Games-type competition, whether we like it or not.” Lucy Wright, Care-fuelled leadership

Unfortunately, most artists will relate to Lucy Wright’s description of how continually pitching as an artist for – and failing to ‘win’ – opportunities and funding diminishes her livelihood prospects and well-being in equal measure.

However good their ideas and PR and application writing skills, individuals operating as independents in the arts – I include myself in this – are at a disadvantage when faced with the hyper-competitive trickle-down economic regimes delivered by arts organisations whose fortunes are all too closely aligned to a funding agency itself at the mercy of a government unsympathetic to ‘art for art’s sake’.

Standardised rates serve freelancers badly

As successive research studies have demonstrated, standardised rates calculated by unions and professional bodies have served freelancers badly. The unintended consequence is that minimum day rates are in general treated as maximums in work offers.

Worse still, any glimmer of personalised artistic development is curtailed by a commissioner’s narrow terms: “… awful brief written like it's a contract for a CEO position and specifying pre-application, unpaid site visits and other set dates and outcomes and the size of your final piece and what it will tell the audience to think with a budget that’s far too small”.

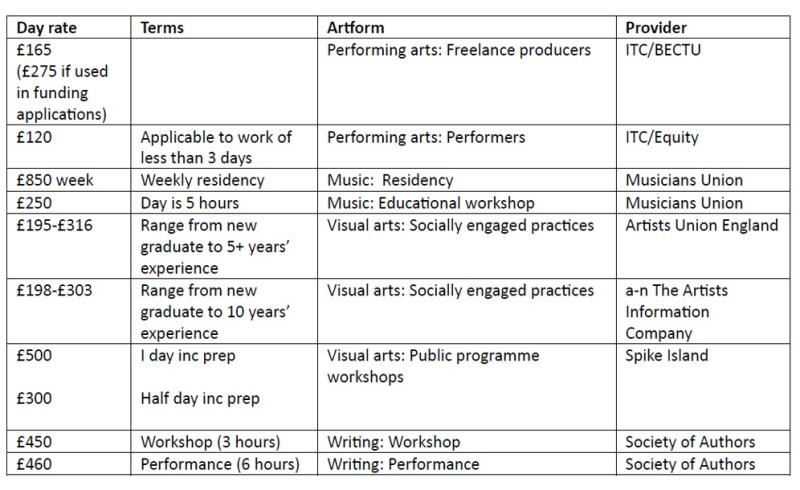

My own review of 2023 pay rates provided by such bodies (illustrated above) highlights the variations in reward levels. Only ITC/BECTU assert forward budgeting figures, addressing the inevitable time-lag between planning and delivery of an arts programme. However, most practitioners report struggling to command even the basic rates, let alone to get their invoices paid in a timely manner (and without unnecessary deductions).

“I’ve shown and performed around 140 times in my career, often with large-scale works, but I’ve seldom commanded an exhibition fee of more than £2,000, a sum that in no way covers the weeks and years spent on developing projects.” Lindsay Seers, artist

Question marks hang too over the exact number of hours in a freelancer’s working day, quite how fixed overheads get covered on meagre fees, and whether artists with family responsibilities can ever really hope to sustain productive, visible practices over a lifetime. It’s ironic – see PEC’s 2021 study – that being entrepreneurial curtails freelance creative careers, while individuals dependent for livelihood on work from funded arts institutions tend to be worse off economically.

Thwarted ambitions

Policy talks up equity and inclusion across and through the arts. But applications demonstrate a lack of curiosity – not to mention of haste – in remedying the well-documented lack of justice when it comes to the daily working conditions and career development prospects of tens of thousands of freelancers making the actual art for public access.

Until the contributions of every individual, regardless of social and employment status, are equally valued and catered for, including through appropriate creative opportunity and tangible reward (including pay), such ambitions will remain thwarted.

After far too many decades of jam tomorrow, artists deserve better than expending their scarce time and money on unregulated experts in the burgeoning arena of ‘artists’ professional development’ just to keep a toehold in the industry – this in any case being fruitless, according to PEC’s research.

FRANK’s approach to effecting fair artists pay is holistic, collaborative and embedded, directly addressing lack of knowledge among curators and arts organisers of what good practice looks like as far as arrangements with individual artists are concerned.

But lasting remedies lie in something more strategic and expansive still. For it is only through adopting pay parity measures – examples include the Socially Just Waging System and CWU’s New Deal for Workers – that all will be nurtured and sustained in making their distinctive contributions to the nation’s arts and cultural successes.

Credits

Commissioned and first published in Arts Professional in April 2024, this text is a companion to Artists' livelihoods: my essential reads, commissioned by the Centre for Cultural Value and published by Culture Hive.