Although not a major aspect of artists’ livelihoods, grants and awards to artists are a vital contributor to sustaining art practices over a life-cycle. This paper starts by outlining the benefits of direct funding to individual artists, describes differing arts policy perspectives on this in England over the last thirty years and provides a case study of Arts Council England’s Grants for the Arts Scheme 2003 – 14 before making an argument for new, nuanced, localised approaches to nurturing and supporting the wider constituency of visual artists and diversity of art practices in future.

Benefits of direct funding to artists

By supporting artistic experiment and risk, direct funding which has the effect of empowering artists generates equitable relationships with others. Glinkowski’s analysis of awards made direct to artists by a charitable trust concluded that value was created in two interrelated ways. Firstly, an artist’s “sense of self” is strengthened by ‘no strings’ funding because the freedom to concentrate on and reflect on art practices heightens their esteem and extends personal and professional relationships. Direct grants are potentially transformative for artists by precipitating a “turning point in their career…. a moment of creative or professional breakthrough or change [with] significant and lasting consequences”. Secondly although they may not improve economic position in the longer term, awards which enable artists to pursue and hone a particular way of working provide a bridge to high-quality opportunities which build professional status and make artists’ practices more sustainable over a life-cycle.

As my own doctoral research has concluded, an underlying value of grants to individual artists lies in their ability to effect a process which results in co-validation. This serves to rebalance power in working relationships and is supportive of equality of opportunity. This is exemplified by Jackson & Devlin who demonstrated how direct grants enabled artists to generate approaches to arts organisations and other collaborators. Larger sums of money not only gave the artists greater control over the direction of a project but “encouraged ambition and innovation.” Louise’s study of grants to artists 2008 – 2010 also confirmed direct funding as strategic contributor to maintaining even-handed, healthy visual arts infrastructures.

“[Grants] give the artist-as-originator greater authority over their own production, artistic direction, budgets, timescales, collaboration partners and project management. It is empowering to the artist, not only giving them control over how and what they make, but also in enabling a more equitable set of relationships with their partners. Whilst it may not be appropriate for every artist and every project, it is a valued, significant and important component of art production.”

Such conclusions align with NESTA whose analysis of the optimal environment for a creative economy identified the value of investing in individuals because “it is creative talent which, ultimately, drives innovation and growth in the creative economy. Policymakers should always weigh the opportunity costs of investments in ‘bricks and mortar’ against the benefits of [such] interventions.” Hinds & Storr’s 2010 review designed to aid Arts Council England’s future thinking on funding to individual artists found ‘full consensus’ for maintaining direct awards from a consultee list which contained just one visual artist.

“The nurturing of individual artists, practitioners and producers is at the heart of investment in the future of the arts. Creativity, whether primary (writer, sculptor) or secondary (actor, musician), lies with the individual. The value of arts organisations lies in their ability to connect individuals productively.”

Interestingly, such perspectives align with DHA and ICM’s 2012 stakeholder research for ACE. When asked ‘who should benefit most from funding?’ almost a quarter of the arts sector felt it should be artists, suggesting a need to rebalance future investment strategies. In summary then, the value of direct, ‘light touch’ grants to artists has two main aspects. Firstly, this enables artists to make progress through art practice, with the potential to generate transformative points of departure and development over the longer term. Secondly, grants to artists foster equality of opportunity and contribute to a healthy balance of power in visual arts infrastructures.

Brief history of grants to artists

In 1985 it was common for the twelve regional arts associations (RAAs) which operated autonomously from Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB) to provide some kind of direct funding to artists. As an example, Southern Arts Association allocated 44% of the visual arts budget to open-access schemes providing direct grants or fees to artists. Eckersley illustrated how artists in that region could access small grants to purchase materials, for framing, presenting and transporting work for exhibitions and occasionally for travel. Such RAA schemes ran in tandem with larger bursaries and major awards such as fellowships that enabled artists to ‘buy time’ in the studio. Even then and aligned with the political environment, the trend was to move away from support for artists’ studio-based research and towards schemes that delivered tangible public outcomes.

Butler identified how Greater London Arts Association shifted direct funding for artists to residency and art commissioning schemes specifically to “stimulate interaction between artist and public”. In Yorkshire Arts Association where the ambition was for artists to ‘show initiative’ and help themselves, resources which had previously gone direct to individual artists were reallocated to groups and organisations providing services for artists. At the national level enhanced patronage of artists was the second objective of ACGB’s Glory of the Garden policy 1985 – 1995. However, due to stand-still government funding, this ambition was deferred as “an important aspiration for the future”.

Direct funding to artists remained a relatively minor consideration in regional and national arts policies until merger in 2001 the national and regional arts bodies to create Arts Council England (ACE). Substantial uplifts to arts funding at the time from a Labour government that was enthusiastic about support to artists combined with enhanced income to the arts from the National Lottery positioned artists “at the centre” of arts policy. ACE’s Ambitions for the Arts policy 2003-06 promised artists “the chance to dream”.

“The artist is the ‘life source’ of our work. In the past, we have mainly funded institutions. Now we want to give higher priority to the artist…. We believe artists, at times, need the chance to dream, without having to produce. We will establish ways to spot new talent; we will find ways to help talent develop; we will encourage artists working at the cutting edge; we will encourage radical thought and action, and opportunities for artists to change direction and find new inspiration.”

Grants for the Arts case study

Grants for the Arts (GftA) was a core feature of ACE’s Ambitions for the Arts policy. It streamlined grant-giving by reducing 100 plus separate application schemes into five funding strands including one specifically for individuals funded solely from government grant-in-aid. Investing in the creative talent of artists one of GftA’s five objectives. This case study provides analysis of impact on artists of this funding stream 2003 – 2014 and highlights the key tensions and ambiguities.

ACE’s supportive regionally-focused structure actively solicited and encouraged applications to GftA from artists, particularly those new to funding. Jackson & Devlin’s evaluation of the scheme’s first year of operation found it “a brave and radical initiative which has transformed Arts Council England’s grant making”. During 2003⁄04, 40% of the value of all grants went to 3,279 individual artists, a success rate of 52%. Of all awards, 50% went to individuals or organisations new to receiving Arts Council funding. 71% of applicants reported ease of using the application process, with over two thirds taking up the opportunity to discuss proposals with regional staff before applying. Significantly, the success rate was almost twice amongst applicants who’d had this personalised advice.

During 2003-08 an average of 1198 artists were funded annually through GftA. Alexander’s examination of funding to individual artists in 2005⁄06 found £8.8 million allocated to nearly 1,600 and the median award £4,700. Fleming, Erskine & Benjamin’s assessment of the 2003 – 2008 period showed that 5,991 artists shared £39,016,927, with almost a quarter of grants for artistic research and development.

Amongst other benefits, Fleming et al concluded the scheme offered “the most immediate, obvious, relevant and flexible investment option for artists that want to innovate” and “it’s flexibility and mobility [and] openness to a wide spectrum of ‘eligible activities’ give it an unparalleled development role, particularly for new/emergent work”. It was equally ‘good’ for the funding body, providing “real reputational value …. engendering confidence, trust and knowledge exchange” and acting as a strategic “building block of creativity”.

“[GftA] offers the most pronounced and visible investment in talent, experimentation and personal development available across the arts in England. Over the last five years, [it] has operated as the primary source of risk investment, seed capital, proof of concept funding and development credit for individuals and organisations across the arts.”

Grants for the Arts analysis 2003 – 2014

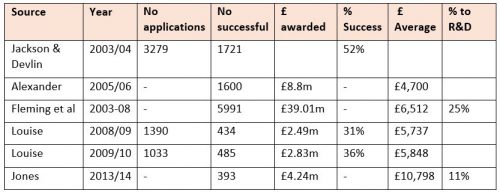

Note that this analysis is from GftA evaluations 2003 – 2014 using available data. Where none is given, this is because it was either not provided by evaluations or not calculable from published data.

This chart shows that while volumes of artists benefiting from GftA remained consistent 2003 – 2008, Louise showed that far fewer artists gained funding by 2008⁄09, with just 485 being successful that year. When compared with 2003⁄04 data, the success rate for artists dropped by sixteen percentage points. The £2,836,152 total allocation to artists 2009⁄10 provides an average award of £5,848, that is to say 10% less than the average award level in 2003 – 2008. At almost one fifth of the total GftA visual arts spend, the total amount awarded to individuals in 2009⁄10 represented a drop of twenty percentage points against 2003⁄04 data.

My own analysis of GftA to individuals in 2013⁄14 indicates that just 393 artists were successful in that year, gaining £4,243,972 in funding, equivalent to an average award of £10,798. Despite GftA’s stated ambition to support artists’ research and development, this accounted for just 11% of awards in 2014⁄15, a drop of fourteen percentage points when compared with Fleming et al’s data.

Tensions

Review of prior research and my new comparative analysis of data has identified two core tensions which impede achievement of the expansive remit set for GftA by ACE as regards support to individual artists.

• Mismatch between demand and budgets

Antrobus concluded in 2009 that demand levels for grants hadn’t ever been adequately assessed or accounted for in direct award schemes, noting that twice as many artists at that time sought grant funding than received support from ACE or from trusts and foundations. Louise concluded that only 5% of artists applied for GftA on their own behalf and that in 2009-10, fewer than 2.5% gained direct funding. In short, the higher levels of demand caused by active solicitation and support from offers for new applicants demonstrated in GftA’s early period were successively reduced to match available funds, in turn substantially reducing success rates. Fleming et al identified the scheme’s paucity of budget as the major barrier to it being “the source of funding for the risky, the challenging and the new.” At less than 20% of Arts Council England’s annual direct investment, over-subscription to GftA was continual, this exacerbated when it was “used to make up funding shortfalls or scale-up other investments”.

• Exclusive application processes

The GftA individual strand was National Lottery funded after 2007. Thus artists had to show ‘public benefit’ and make a 10% cash contribution in their applications. Notably however, Fleming et al concluded that both artists and organisations felt intimidated by GftA application processes and more should be done to ensure that the scheme is “demystified and genuinely opened up”. Beyond the initial period when personalised support for applicants was readily available from regional arts officers and newcomers to funding fared well, research by Alexander and Rosenstein separately concluded the nature of GftA application processes better suited artists with existing track-records who had already secured supportive ‘infrastructures’ around them.

Hinds & Storr’s consideration of the application processes found them better suited for organisations, while being time-consuming and counterproductive to expanding art practices of individual artists. Requirement to show ‘public benefit’ undermined the confidence of some artists who were made to feel like failures when unable to do so. One recommendation was that GftA application processes were made simpler for individuals so that unsuccessful bids didn’t cost them unreasonable amounts of time, effort and money.

In 2016, ACE introduced the online grants management portal Grantium for all funding schemes, this designed to reduce overheads. However, artists reported the new platform counterintuitive and unwieldy to navigate. Artists such as Sonia Boué who are neurodivergent felt they bore the brunt of these cost savings with their own unpaid time. Grantium’s “language is … often jargonistic and hard to read or make sense of. It also speaks to artist applicants and arts organisations as though they were one and the same thing.”

My doctoral research 2015 – 2019 aligns with Alexander and Rosenstein by finding that the artists who fared best with GftA had already developed personalised, supportive infrastructures. They had existing experience in writing fundraising applications and knew how to access advice from arts professionals, including informally from ACE officers. They had often previously been awarded funding, so understood how to generate partnerships with funded arts organisations in applications and could as a result show the necessary budget contribution.

Developing your creative practice

In 2018 when GftA ceased operation, ACE launched Developing your Creative Practice. This new scheme is funded through grant-in-aid and thus is free from the National Lottery restrictions which hampered GftA’s ambitions to support the individualised research and development of many artists. DYCP offers creative practitioners inclusive of “dancers, choreographers, writers, translators, producers, publishers, editors, musicians, conductors, composers, actors, directors, designers, artists, craft makers, and curators…. that most precious of things – time” for research and development, with no obligation to produce anything at the end”.

In monetary terms however, the annual DYCP budget allocation of £3.6m for all these eligible ‘creative practitioners’ is not reflective even of GftA’s lower success levels for artists in 2014⁄15. In effect, DYCP’s entire annual budget for all ‘creative practitioners’ amounts to 15% less than the figure awarded to individual visual artists through GftA in that year. My own early analysis of comparative data suggests that whereas between 393‑1991 visual artists a year benefited from GftA 2003 – 2014, in a twelve-month DYCP period just 135 visual arts practitioners including artists, producers and curators shared £1.21m.

This represents 28% of the £4.24m awarded to visual artists through GftA in 2013⁄14. The average DYCP award of £8,992 is almost 17% less than the average GftA award of £10,798 in that period. The decline in volume and value of direct funding to artists from ACE is unambiguous. In 2009⁄10 fewer than 2.5% of artists were directly funded by GftA, but by 2013⁄14 this reduced to less than 1%, with DYCP showing a further decline.

The future of direct funding to artists

This paper demonstrates the vital contribution of direct grants to artists to sustaining and transforming artists’ practices over the longer-term. However artists’ ambitions in this respect are constrained by Arts Council policy and associated lack of budget. Although the Ambitions for the Arts policy supposedly offered artists the ‘chance to dream’ more than a decade ago, the volume of artists benefiting from direct funds 2003 – 2015 and sums allocated to their support have successively diminished.

Both Fleming et al and Louise argued that allocating a bigger slice of the funding cake to individual artists in recognition of their contribution to social well-being was not a radical proposition. Devolution of either all or solely the small grants aspect of GftA to appropriate external agencies for distribution to artists was also proposed previously by Hinds & Storr although ACE has as yet chosen not to pursue this.

As part of a substantial ‘rebalancing’ of arts funding to better reflect the diversity and nuances of the arts across England Stark, Powell & Gordon proposed artists should be made a distinct ACE funding category and a 20% share of all National Lottery funding to ACE allocated to “programmes available to individual artists and arts-led projects to encourage new talent, diversity, innovation, and excellence in work locally, regionally, nationally and internationally”. Rather than the £3.6m per annum offered through DYCP, using such a formula for 2018 – 22 would have made some £49.26m a year available for direct and indirect interventions supportive of artists’ individualised development.

To similar ends, the Campaign for Cultural Democracy (CfCD) proposed a transaction tax on the UK’s art market to create an extra £1b government grant-in-aid to the arts including to artists working locally in communities. Such de-centralised, amplified funding would be allocated by regionally-representative, democratically-structured and administered bodies intended to empower communities concerned and – relevant to artists – and prioritise “investment in people over products, process not results.” Standing’s notion of a Commons Fund as a redistributable localised wealth resource drawn from a tithe on empty property and the European Union’s for a tax on global digital companies are in the same vein. Whatever the source of funding, a conclusion from my research is that nuanced, localised approaches are more effective for nurturing and better supporting the wider constituency of visual artists and diversity of art practices over a life-cycle.

In terms of improving equality of opportunity for artists, it is preferable for policy measures to directly relate to and support heterogeneity within the artists’ constituency. In this way, funding instruments contribute more effectively to artists’ livelihoods by enabling them to better exploit their rights and manage changing external trends and shocks. Significantly, absence of these personalised, supportive frameworks is known to diminish people’s potential by wasting their drive and creativity.

References

This text extends the analysis and commentary in my doctoral thesis Artists’ livelihoods: the artists in arts policy conundrum, 2019 available at http://e‑space.mmu.ac.uk/62635…

Antrobus C. (2009). The funding and finance needs of artists. London: Artquest (UAL)

Alexander V. (2007). ‘State Support of Artists: The Case of the United Kingdom in a New Labour Environment and Beyond’ in The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 37:3, pp. 186 – 200

Arts Council England. (2003) Ambitions for the Arts 2003-06. London: Arts Council England

Bakhshi H, Hargreaves I, & Mateos-Garcia J. (2013). A Manifesto for the Creative Economy. London: NESTA.

Brighton A, Parry J, Pearson. N.M. (1986). Enquiry into the Economic Situation of the Visual Artist. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Butler D. ‘Buying Time’. Artists Newsletter, July 1985 pp. 24 – 26. Sunderland: Artic Producers.

Developing your Creative Practice. London: Arts Council England https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/DYCP

DHA & ICM (2012). Arts Council Stakeholder Focus Research. London: Arts Council England

Eckersley S. ‘A new broom’, Artists Newsletter, October 1985 pp. 21⁄22. Sunderland: Artic Producers

Editorial, ‘ACGB’s New Strategy’, Artists Newsletter, May 1984. Sunderland: Artic Producers p. 2.

Fleming T, Erskine T & Benjamin A. (2010). Evaluation of Grants for the Arts 2003 – 2008. London: Arts Council England

Glinkowski P (2010). Putting Artists in the Picture: Locating visual artists in English arts policy and in the evidence-base that informs it. Doctoral thesis, University of Surrey.

Hinds N & Storr S. (2010). Grants to individuals: Report 28 May 2010. London: Arts Council England

Jackson A & Devlin G. (2005). Grants for the arts: evaluation of the first year, Research Report 40. London: Arts Council England

Jones S. (2017). Analysis of GftA 2014⁄15 (unpublished)

Louise, D (2011). A fair share? direct funding for individual artists from UK arts councils. Research Paper, a‑n The Artists Information Company www.a‑n.co.uk/research [accessed 15/04/2018]

Manifesto for Cultural Democracy. https://culturaldemocracy.word… [Accessed 12.12.2018]

Rosenstein C. (2004). ‘Conceiving Artistic Work in the Formation of Artist Policy: Thinking Beyond Disinterest and Autonomy’ in The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 34:17 pp. 59 – 77

Standing, G (2018). ‘Rentier Capitalism and the Precariat: The Case for a Commons Fund’ in McDonnell, J Ed. Economics for the Many. London & Brooklyn: Verso. pp. 195 – 206

Stark P, Powell D & Gordon C. (2014). The PLACE report: Policy for the Lottery, the Arts and Community in England.