Effective strategies for retaining the artist-led as a vital ingredient in social and arts well-being in future involves artists seeking out allies and synergies beyond the restrictive hierarchies of the contemporary visual arts.

Action by groups of artists driven by collective artistic aspirations has punctuated the contemporary visual arts landscape over the last fifty years. Through joint — sometimes ‘alternative’ – ventures, artists’ practice-driven interests have provided dedicated means for testing and extending the scope for interaction with artistic collaborators and communities of interest, including with spectators for and buyers of contemporary art. Artists’ initiatives raise status and expand remit through such engagements, while also contributing to widening understanding of the artist’s role in society. Although outcomes differ in form and intention, the commonality between such artists’ groupings is persistent commitment to working through the processes of making art, forging productive relationships with others and desire to amplify engagements with their immediate constituency as well as with broader communities and society. Products of artist-led initiatives range from works by individual artists presented collectively in exhibition or site-specific format to collaborative art works and manifestations in which the artists’ social engagement with other people is core. As part of the financing of the latter, artist-led initiatives iteratively define suitable organisational and ‘business’ models for their particular circumstances. In these artist-led spheres of operation, social and economic benefits to artists accrue over time and contribute to sustaining their art practices and livelihoods over a life-cycle.

In the ‘arts as regeneration’ era since the ‘80s, artist-led ventures have been key contributors to building the UK’s cultural identity and contemporary visual arts infrastructures. London’s now renowned concentration of artists’ studios began in the ‘60s when groups of artists took over St Catherine’s Wharf. It continued steadily through the energies later of artists’ initiatives Acme and SPACE, in effect gentrifying run-down areas of the capital and providing a model later emulated by other cities. These organically-grown ventures suited arts funders who cherry picked and talked-up the aspects of the artist-led which are more palatable to, and measurable by, economics-based arts development yardsticks and are more easily cross-referenced to existing traditional institutional infrastructures.

Brighton, Parry and Pearson’s seminal 1985 exploration of artists’ economic status located their propositions for improvement firmly within the traditional gallery and art market systems. Greater support by funders for artist-led organisations including galleries and group studios to ‘mediate their own reputations directly with the public’ was justified because this contributed to preserving dominant art market and art world patterns. The National Lottery’s massive new income streams for the arts from 1994 promised to transform the cultural landscape and provide greater levels of support for artists working in the public realm, including by putting more public funding to the artist-led.(1)

The lottery’s Art for Everyone strand gave £100,000 (equivalent to £213,000 nowadays) to MART artists’ initiative for month-long, city-wide ‘festival of visual art made in Manchester’. At the turn of the Millennium, Williams’ analysis likened post-industrial Manchester to ‘60s New York, with ‘plenty of slack in the system’ including an abundance of cheap live and work space for emerging artists and artist-led initiatives to appropriate. MART’s eight-strong organising group that brought together independent artists with others from the city’s studios including SIGMA, Manchester Artists Studio Association, Rogue and Bankley Studios argued that the low profile of visual artists was a ‘cultural gap’ that needed filling in a city already renowned for performing and media arts, science and sports. Unlike the 1995 – 96 multi-site exhibition ‘British Art Show 4’ that preceded it and that relied on incoming artists, MART’s projects and exhibitions were explicitly home-grown. More specifically MART intended to ‘reveal the sheer strength and diversity of artistic practice…. and make the work of Manchester’s visual artists visible and available to all’.

Notably, MART’s overarching ambition to create temporary manifestation that would catalyse a sustainable network of practitioners and act as a departure point for collaboration on future city-wide festivals with the established art institutions such as Cornerhouse (now HOME) and Manchester City Art Gallery on equal terms remained unrealised. The cohort of newly-graduated photographers who in the same period initiated the ‘New Exposures’ festival in seventeen traditional and ad hoc spaces were however more successful in creating legacy. The aspiration to support and retain practitioners in the region beyond graduation was later realised through Redeye, the professional network and a membership body for photographers now in receipt of regular funding from Arts Council England. Such examples illustrate Wright’s assertion that the connective tissue sustaining artists’ initiatives is the strong friendship born out of the camaraderie of student life.

Arguably, informality and temporality are vital characteristics of collectively-realised initiatives where retaining artistic integrity and fluid modus operandi are prime drivers. TEA – a collaboration between four new graduate artists in late ‘80s Manchester took the novel approach of establishing each process- and place-based investigation as a ‘temporary institution’ that encompassed the interests of all collaborators. The unifying ‘brand’ was a practice-led, collaborative research methodology with meticulous planning structures individualised frames of reference and targeted production and distribution mechanisms. This strategy enabled TEA to gain the equivalent of £123,000 nowadays in public funding while avoiding the dampening impacts of adopting a traditional, charitable organisational structure. The success of these artists-led temporary ventures led some of the (then) regional arts boards in England to solicit ideas from groups of artists for Regional Arts Lottery Programme (RALP) funding. As example, North West Arts Board’s Working with Artists Franchise Scheme from 2000 reported on by Stanley offered three-year funding of up to £100,000 a year to artists’ initiatives, with decisions notably made on quality of work rather than instrumental value.

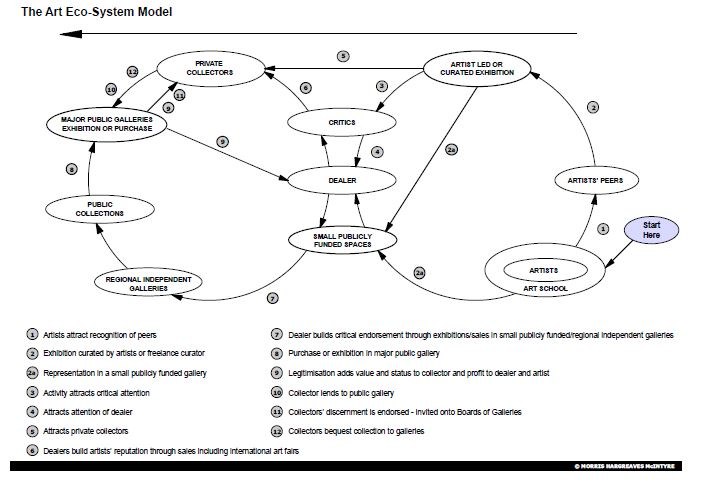

These examples demonstrate how funding interventions capture and appropriate the artist-led as means of rationalising what artists can do for arts policy ends. Funders benefit from being part of the frisson an ‘alternative label’ brings, while they anchor and confine the scope and granularity of the artist-led back into the institutionalised practices they like best. An example is the argument for greater support of artist-led initiatives that emerged from Morris, Hargreaves and McIntyre’s 2004 study of the markets for art. In what was dubbed as a ‘golden age’ for the arts with massive expansion of the physical infrastructure for the arts, a Labour government increased grant-in-aid to the Arts Council by 70%. Expanding markets for art beyond London in cities with virtually no infrastructure for selling critically engaged, innovative, contemporary art became a holy grail for arts policymakers. On economic arts policy grounds, artist-led galleries, open studios, art fairs and festivals were valued as prime vehicles for accessing the £515m in retail sales of contemporary or ‘cutting edge’ art. Widening access to this untapped income source would have the effect of ‘bringing on’ emerging talent without upsetting the fine balance of the commercial art gallery subscription model eschewed by arts policy. The effect of this gatekeeper mechanism which arbitrates between ‘art’ and ‘decoration’ otherwise discourages artists from selling to unauthenticated buyers. (2)

Morris, Hargreaves and McIntyre’s Art Eco-System Model demonstrates that selected artist-led galleries might be worthy candidates of public funding in recognition of their discrete role in this respect. Moves on contemporary visual arts courses to encourage undergraduate students to form groups and work collaboratively, as identified by Rowles’ 2013 study could similarly be construed as an economics-led solution by demonstrating the ‘employability’ and career development arising from higher education courses. In the same vein, Manchester School of Art actively supported students on graduation to form the DIY Art School as a peer network and ‘fourth year’ of their course.

While playing to the blunt instrumentality of an economic art model, these neat delineations of the scope, purpose and impacts of artist-led practices belie a heterogeneity of social benefits. My 1995 study of 300 artist-led groups demonstrated value created in various ways, whether divergent from or synergous with arts policy imperatives of the day. The majority provided groups of artists with the ‘means of production’ in the form of collective workshop and studio space and joint marketing initiatives as practical support to artists’ individual practices and livelihoods. In just under a third however, artists’ individualised aspirations for art practices were superseded by forging collaborations premised on wider social activism and engagement. As example, London-based Platform’s interdisciplinary work was driven by ecological and social imperatives. This alliance of video and performance artists, musicians, engineers, social historians and green economists later became renowned for the Artwash campaign that successfully stopped BP sponsorship of the arts.

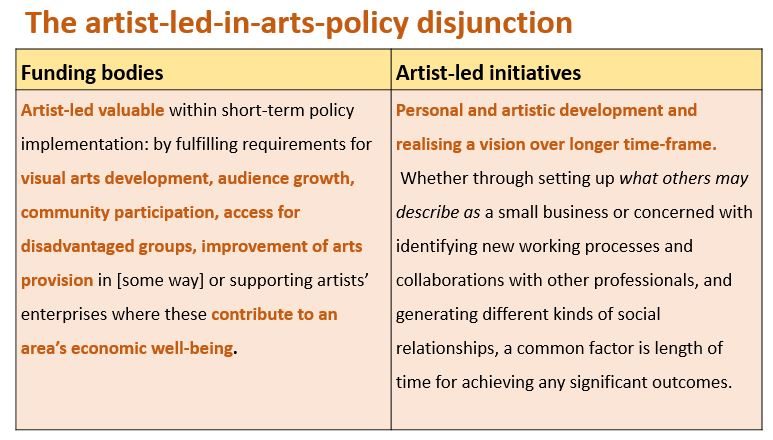

Although these divergent types of artist-led venture bring nuanced values to artists’ pursuit of art practices over a life-cycle, the tendency of funders in the UK’s ultra neo-liberalist arts economy model is to give preference to public-facing ventures with readily measurable ‘outcomes’ such as earned or philanthropic income and audience volume. Reanalysis of my own study data highlights the baseline disjunction between the intrinsic values that underpin and sustain artists and artist-led practices and arts policy’s instrumentalised measurements.

As Adams and Godbard concluded, funders’ preference is to deal with organisations which look and act like they do, including speaking their language. Grant-givers ‘tend to be organisational technocrats… treating management structures and techniques as handy, value-neutral tools for making things happen.… [judging the] board-led structure [as] the best tool for getting just about any job done’. The artist-led in arts policy disjunction is colour-illustrated by the funding decisions made by Arts Council England 2010 when faced with substantial cuts to government grant-in-aid. Louise’s analysis revealed that axing sixteen small-scale, artist-led organisations including production facilities, artist residency providers and membership groups affected the art practices and livelihoods of almost 6,700 visual artists. When push came to funding shove, these artist-centred ventures were judged of far lesser importance than the ‘frontline’ institutions who interface face-to-face with, and derive economic benefit from the public.

Many of the forty-seven organisations categorised and funded by ACE as ‘artist-led’ since 2018 as National Portfolio Organisations (NPOs) are permanent, building-based charitable organisations. As pragmatic move to keep artists’ divergent artistic imperatives ‘in the game’, such artist-led groups are unwitting supporters of a biased and unfair art system for artists. Research by Thelwall and by De Mynn both proposed how ‘insider’ small-scale and artist-led organisations might use their influence with funders as leverage to change an imperfect system for the better from within. They could collect evidence and advocate wherever they could for their ‘alternative’ organisational approaches, as mechanisms for capturing artists’ unseen ‘outputs’, as vital divergent contributions to society. However once in the ‘regularly-funded’ arena, smaller and artist-led organisations can inadvertently become complicit in the ‘rules’ of contemporary visual arts that stifle dissent and keep most artists ‘in their place’, at the bottom of the arts food chain. They condone the inequalities of the mediating and gatekeeping protocols that characterise the workings of the contemporary visual arts, including accepting unfair treatment of artists through poor pay and conditions, lack of meritocracy and creeping levels of preference for the recommendation route over open submission. The price of reliable funding for these organisations is having their ideas pinned down and categorised, only accounted for when outcomes are easily measurable, all requirements that may distract from what supporting artists’ practices is really about. But in any case, funding to this aspect of contemporary visual arts is minor as only 11% (or £4.8m over a 4‑year period) of ACE’s entire visual arts NPO budget goes to regularly-funded artist-led organisations.

In such contexts and as Nichol observed, the gap between artists’ and funders’ needs and intentions nibbles away at the rigor of artists’ practice-focused ethos. Being funded serves to endorse and encourage only certain aspects of artists’ activity. Unhealthy levels of exclusivity and preciousness are unintended consequences of being lead in funding-focused directions. Encouraging practice-led organisations to adopt the bureaucratic structures of bigger organisations is restrictive of ad hoc and alternative, creative approaches to achieving artistic ends. Serving the different perspectives and expectations of funders and board members is a time-consuming distraction to maintaining core principles. In short, ‘Making a commodity of practice-led activity … impacts on artists by altering the nature of their activity or [sustaining poor] conditions’. Goodman’s story encapsulates what artists can’t talk about, and how this condones unhealthy conditions and relationships in contemporary visual arts. Although feeling ‘fucking pissed off’ at losing the space the group had invested in over time at short notice, his emotional precarity was automatically reframed into the positive language characteristic of art world resilience. Adopting the ‘talking up’ that pervades arts communications, he fell into ‘performing the role’ the art world expected of him. In reality he felt ‘kicked in the teeth’ but his external communications belied it. In translation, the artists were instead ‘excited for what is next’, relishing the ‘opportunity to reflect on what we want to do and build something better’.

In terms of identifying a more substantial, influential position in the arts ecology in future, artist-led groups might take a leading advocacy role to policymakers by generating a stream of evidence about artists’ social conditions and the nuanced impacts of their practices on society. Despite being located in the lowest tier of the Arts Council’s NPO hierarchy, funded artist-led organisations have opportunity through regular communication and reporting to ensure ACE is aware arts policy’s positive and negative impacts on all artists’ ability to sustain practices over a life-cycle. Although it is commonplace in other countries and nations for artists’ representative bodies to take this strategic advocacy role, attempts to sustain a credible traditional artists’ membership body in England have consistently failed to gain popular support.(3)

As redress and as invitees to policy-making fora, NPO artists’ organisations could take responsibility for bringing insights and experiences of the wider artists’ community into various fora where decisions that affects artists’ social status are made. However even if they did chose to pursue this ‘greater good’ remit, NPO reporting arrangements restrict opportunity for collecting such nuance of evidence and depth of advocacy. Rather than articulating values and outcomes arising from the distinctive and nuanced role of the artist-led in enabling artists’ practices and livelihoods, NPO terms of reference are mechanistic, focusing predominantly on measuring public-facing impacts such as audience volumes and demographic.

Overtly social activist artist-led group such as Platform were able to attract grant-aid in the past from a regional arts board for work that was inherently politically awkward. In the ultra-conservative, risk-adverse environment for the arts today, micro and practice-led initiatives dedicated to progressing unambiguous critique of the status quo are far less likely to be ‘seen’ or to gain access to short or longer-term public funding. The situated practices and energies of artists’ initiatives at the turn of this century played a significant role in reimagining post-industrial Manchester as the creative and cultural hub it now is. My own definition for situated practices in this respect is those that are conceived, developed and modified by artists over time in relation to artistic ambitions which encompass their personalised circumstances including where they live and family contexts. With the notable exception of Castlefield Gallery, artist-led ventures in Manchester get scant support from the arts infrastructure to remain or set up there nowadays. The artists’ studios pivotal to MART’s critical edge and cultural relevance have since been allowed to close or forced to migrate to the periphery. Rather than on strategically nurturing the indigenous artists’ community, the high status enjoyed by the city’s ‘top tier’, large-scale NPO arts institutions rests nowadays on their success in importing internationally-accredited talent.

I’d argue that locating effective strategies for retaining the artist-led as a vital ingredient in social and arts well-being in future involves artists seeking out allies and synergies far beyond the restrictive, disempowering hierarchies for contemporary visual arts. Whether transient or sustained, frameworks and kindred spirits most welcoming and supportive of artists are more likely to be found close to where they reside. Hyper-local initiatives exemplify the richness and resilience of embedding socially-engaged and place-based artist-led interventions and collaborations into specific communities. Deveron Arts in Huntly, Scotland has used the town and 4,500 population as resource and venue over the last twenty-five years. Artists of all disciplines come from around the world to live and work there, using supermarkets, streets, churches, garages and bothies around and about as studios and sites. In a similar vein, artist-led In-Situ’s vision is to ‘allow art to be a part of the everyday life’. Ambitions are to foster resilience and innovation across their Pendle community, so all people ‘speak and act with confidence’ and are actively engaged in their cultural futures.

More laterally, clues about structural remedies to artists’ integration in social change that enable artists as citizens to be both seen and heard are emerging from artists’ direct interventions into localised policy-making. Preston’s Brewtime Collective is integral in developing the city’s 12-year cultural policy, this within the artists’ overall ambition to create a sea-change that ‘embeds cultural experiences in the lives and expectations of all the people’. In the new Mayoral constituency of West Yorkshire artists are prominent, their voices heard loud and clear. There, the strategic processes and consultations emanating from Same Skies Think Tank are developing new, situated arts and cultural policy from the ‘bottom-up’. These few topical examples are part of a burgeoning of progressive actions by and with artists. They are indicators of the conditions enabling artists to be both seen and heard, and could – at long last — achieve Redcliffe-Maud’s 1976 aspiration for arts policy measures that are truly representative of the constituencies they serve by ‘foster[ing] individual creativity and … bring[ing] the results [of that] before the public’.

Commissioned and first published by Sluice, 2021, this text draws on the author’s studies Refreshing alternatives (1995) and Measuring the experience: the scope and value of artist-led organisations (1996).

Notes

(1) Support to artists as a key aim for National Lottery funding is stated for example in Public Art in the North – a strategic approach to public art and lottery funding, Northern Arts Board paper, 1995.

(2) Morris, Hargreaves and McIntyre’s study identified mechanisms for, and barriers to, accessing an untapped £354.5m market from sales in the traditional gallery-based art world and £515.5m from work sold through ‘non-legitimised’ channels including art fairs, shops and studios.

(3) Reportage of this Platform campaign is at https://platformlondon.org/p‑publications/artwash-big-oil-arts/

References

Adams, D, and Goldbard, A. (1992) Organising Artists: a document and directory of the national association of artists’ organisations, National Association of Artists’ Organisations, USA.

Brewtime Collective https://somethingsbrewing.org.uk/brewtime/ [Accessed 3rd March, 2021]

Brighton, A., Parry J. and Pearson N. M. (1985) Enquiry into the Economic Situation of the Visual Artist. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

De Mynn, R. (2016) Artist Development at Castlefield Gallery: Policy Change through the Counterpublic? Manchester: Castlefield Gallery Publications.

DIY in Manchester, a‑n The Artists Information Company, 2013 https://www.a‑n.co.uk/news/diy-in-manchester-like-a-fourth-year-of-art-school/#:~:text=Although%20formed%20just%20a%20few,social%20experiment%2Fart%20club [Accessed 3rd March, 2021]

Goodman, D. (2020) What we don’t can’t talk about when we talk about the artist-led, January 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTtLzA2cQtI [Accessed 3rd March, 2021]

Jones, S. (2019) Artists livelihoods: the artists in arts policy conundrum, PhD thesis Manchester Metropolitan University, 2019. http://e‑space.mmu.ac.uk/626357/

Jones, S., Art in everyday life, Arts Professional, 2015 https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/285/case-study/art-everyday-life [Accessed 3rd March, 2021]

Louise, D. (2011) Ladders for development: a‑n Research paper. Newcastle: a‑n The Artists Information Company.

Mart 1999, The Mart Group Application March 1998 and MART Network: A festival of visual art made in Manchester. Project Evaluation.

Morris, G, Hargreaves, J, and McIntyre, A. (2004) Taste Buds: How to cultivate the art market. Executive Summary. London: Arts Council England.

Stanley, M. ‘The mid-life crisis and artist-led initiatives’, a‑n Magazine, June 2000.

Glinkowski, P. (2010) Putting Artists in the Picture: Locating visual artists in English arts policy and in the evidence-base that informs it. PhD thesis, University of Surrey.

Nichol G. Introduction, Mind the gap, a‑n The Artists Information Company, July 2003 https://www.a‑n.co.uk/resource/mind-the-gap‑1/

Rowles, S. (2013) Lay of the land, a‑n The Artists Information Company, https://static.a‑n.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/3171032.pdf [Accessed 3rd March, 2021]

Same Skies Think Tank https://sameskiesthinktank.com/

Stanley, M. ‘The mid-life crisis and artist-led initiatives’, a‑n Magazine, June 2000.

Thelwall, S. (2011) Size Matters Size Matters: Notes towards a Better Understanding of the Value, Operation and Potential of Small Visual Arts Organisations. London: Common Practice.

Williams, R. J. (2001) ‘Anything is Possible – The Annual Programme 1995−2000’ in Life is Good in Manchester: the Annual Programme 1995 – 2000, Ed S. Grennan, Trice Publications.

Wright, J. (2019) The Ecology of Cultural Space: Towards an Understanding of the Contemporary Artist-led Collective, PhD thesis, University of Leeds.