“This is a moment fraught with possibility.” Isabelle Tracy, Parallel State: State of the Nation podcast 27 March 2020

This text in the Covid19 portfolio is on the future of artists’ livelihoods. It starts by evidencing the impact of external trends on visual artists’ livelihoods. It then identifies some of the policy misassumptions and structural barriers that limit artists’ livelihood prospects before demonstrating that visual artists as a ‘special case’ within the arts workforce are deserving of individualised attention within arts policies. It concludes by outlining the core qualities for pursuit of livelihoods through art practices that enable many artists to contribute to society over a life-cycle as a point of reference for policy-making during the Covid19 emergency and into the uncertain decade ahead.

Artists’ livelihoods and changing trends

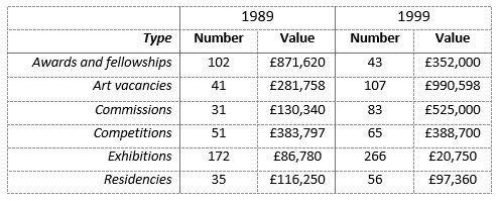

If you track the volume and value of openly-offered to artists as I’ve done for over 30 years, it’s clear that visual artists’ livelihoods are consistently affected by external economic and arts policy trends. Here’s an illustration:

Artists’ opportunities comparing 1989 and 1999 from a‑n (2004)

This chart shows that in 1989, the combined traditional areas of awards and fellowships, competitions and exhibitions represented 56% of volume of all work and 70% of value. Artists characteristically pursued studio-based practices, applying for awards and fellowships to make new work and distributing finished pieces through exhibitions and submissions to opens, prizes and competitions. Although only 5% of all opportunities, the expanding field of commissions was attractive to artists, this in part because of the considerably larger budgets.

A decade later, although remaining 43% of total volume of all work, the traditional opportunities areas of awards and fellowships, competitions and exhibitions reduced to just 30% of overall value. Art commissions had increased to 20% of overall value of all work offered to artists. These opportunities within percent for art schemes and major public art programmes attached to regeneration of waterways, cycle paths, tramways and transport systems were often supported by the (then fairly new) National Lottery funding (a‑n, 2004).

Looking back at past government and arts policy practices illustrates that these aren’t necessarily ‘bad’ for artists. Here’s two examples.

- Artists whose practices incorporate public art commissions have consistently earned better incomes than practitioners in other visual arts genres such as fine art exhibitions and sales. Whereas galleries rarely differentiate, public art commissioners expect to pay to get artists with sufficient experience in the field (DHA, 2013; Baines and Wheelock, 2003; Ixia, 2012).

- Working with Creative Partnerships (2003−11) improved the livelihoods of 3,500 dual career artist-educators. The regular, part-time work provided financial stability for dual career artists who were paid at fair market rates (BOP, 2012).

As this artist’s account shows, artists weren’t merely providers of a service to Creative Partnerships’ distributed agencies though because the work was complementary to personal practices. “Sharing our creative processes with young people was invaluable for us and them. I still come across some of the kids I worked with all those years ago, who tell me they remember what we did and how much they enjoyed it.”

Impact of 2008 economic crash on artists’ livelihoods

Do it all, for artists’ sake, now demonstrated the devastating, lasting impact of the 2008 economic crash on artists’ livelihoods and how the recession and austerity period that followed irrevocably affected artists’ work prospects. In summary, the loss in relative value of openly-offered opportunities in 2016 was nearly £12m. Here’s two illustrations of what 2008 felt like for artists.

“Things started so well for me when I left university. I walked straight into selling work through commercial galleries and right from the beginning, I could be an artist full-time …. Then came the financial crisis when commercial galleries were struggling to sell. In no time at all, I went from a position of supporting my life quite easily through my artwork to being not able to at all.”

“In 2008… with no notice at all, a regular freelance contract dropped from £200-£300 a week to next to nothing and there were no big projects coming my way at all.”

But rather than ‘give in’ to the daunting environment, such artists instead devised highly-personalised approaches to navigating through the difficulties they faced. Later on in the text there’s an explanation of the qualities these artists developed that enabled them to sustain themselves artistically and economically into the decade beyond.

Debunking arts policy assumptions

Although to a lesser or greater extent Arts Council England in its various incarnations has intervened in support to artists over the last 30 years, it’s consistently been a minor aspect of overall provision. In the austerity period, Arts Council England’s policy for arts preservation moved as far away from supporting individual artists as it could.

The majority of National Portfolio Organisations (NPO) funding for 2012 – 15 went to public-facing, building-based organisations which ACE judged “directly made art” and “the most significant contribution to our goals”. What ACE termed as “some agencies with more of a support function”, such as art form membership bodies and artist-led production facilities and commissioning bodies, were cut entirely (a‑n, 2011). Any support there is now for artists from Arts Council England is premised on three underlying policy misassumptions.

- Funding a few artist-led organisations doesn’t deliver support to many artists

Increased financial support for artist-led initiatives was eminently possible thanks to National lottery funding from 1994. The Arts Council and the former regional arts boards in England actively solicited applications from artist-led ventures for permanent new studio buildings and galleries such as Spike Island, as well as for temporary art festivals such as the 1999 MART contemporary. But when faced with austerity funding levels from government, ACE cut regular funding entirely to a layer of small-scale, artist-led organisations whose activities impacted on almost 6,700 visual artists (Louise, 2011). This illustrated how “ACE clearly misunderstood and underestimated” the value of such initiatives “… by asserting that cuts would only leave gaps in … visual arts sector advocacy and leadership” (a‑n, 2011).

Although 11% (£4.8m over a 4‑year period) of ACE’s NPO (National Portfolio Organisations) visual arts budget is now allocated to artist-led organisations, reporting parameters are better suited to measuring audience type and levels in mainstream public-facing venues. There is thus no systematic data collection by artist-led organisations or funder of the nuanced or less tangible benefits, such as contributions to sustaining artists’ practices and livelihoods over a life-cycle, or of direct or indirect impacts on their communities of interest. Neither are funded artist-led organisations charged with providing a strategic ‘voice’ for artists to policy-makers, nor do these necessarily take an advocacy role for all artists that is to say, over and above the relatively few with whom their programmes directly engage.

- Professional development schemes have limited impact

A key barrier to sustaining artists’ practices is lack of ‘timely and affordable’ professional development opportunity (TBR, 2018). But rather than supporting their individualised aspirations and progression, artists may perceive publicly-funded professional development schemes as variously, too daunting, too ‘schmoozy’, too expensive monetarily and their time, or the advice too generic. Here’s some artists’ perceptions in illustration.

“I’m not an extrovert and I don’t thrive in big bustling situations and if you put me in an environment with too big a group of people I become a wallflower, so I don’t do a lot of networking.”

“ [It] feels to me like if you’re not part of this club or this studio or not paying this fee to get a circle of opportunities, then you may as well just fuck off.”

“[T]he advice I got was formulaic … They probably said the same things to most artists.”

Most artists’ preference is to develop their community of practice and build engagements for it where they are (Markusen, 2013; Speight, 2015). However, many publicly-funded professional and artistic development opportunities may be inaccessible for artists, particularly those with regular child or eldercare responsibilities.

“I’m responsible for my family .… I don’t like to think about being away from home for more than a couple of days at a time. I want to be a good father, taking my daughter to school every day.”

“I’m not from a privileged background, so even if I … was able to travel to other places, I’d [need to be financed].”

- High levels of competition are inevitable and healthy

Anecdotal evidence indicates an increasing reliance on recommendation to identify artists for publicly-funded exhibition and commission opportunity. Being on the radar of nominators is dependent on artists first having the opportunity to become visible. But the ‘Catch 22’ here is that to ‘get noticed’ and achieve artistic success on merit, artists need first to have work shown in exhibitions and discussed by peers, other artists, critics, curators and academics (Jones, 2017; Bowness 1989).

Decline in openly-offered exhibition and competition opportunities in favour of the recommendation route contributes to discrimination — such as on gender, ethnicity and social class grounds — that publicly-funded arts organisations are committed to eradicating. Handing on employment opportunities through recommendation or within a ‘club culture’ exacerbates inequality of opportunity across the creative industries as a whole because individuals’ ability ‘get on’ is dependent less on merit and more on ‘network sociality’ (McRobbie, 2002). Here’s an illustration:

“I know there are curators who get to recommend artists for the ‘closed’ bursaries and commissions, you know, that only artists who are invited can apply for. Obviously, they don’t want hundreds and hundreds of applications to look at, but I do worry that it makes everything about their taste in artists.”

Structural barriers

Do it all, for artists’ sake, now outlined the specificities of visual artists’ livelihoods, characterised by low income, high self-employment levels and inherent limitations attached to acquiring work and opportunity to succeed. An exceptional case: artists and self-employment demonstrated how the ambiguities attached to this status – as held by 77% of visual artists — impacts on livelihoods (CCS, 2012). Two conditions created by arts policy further exacerbate artists’ ability to sustain livelihoods through art practices.

- Business models adopted by funded organisations as a resilience requirement of funding are detrimental to artists’ pursuit of livelihoods

Organisations cannot (or chose not to) afford to pay industry rates for artists’ various programmes inputs — such as exhibitions, gallery education and participatory and outreach. They are neither willing to pay rates reflective of artists’ production and living costs nor to acknowledge financially the interrelationship between artists’ contributions to public engagement and their business resilience (DHA, 2013). That 28% of all openly-offered awards, commissions, competitions and residency opportunities don’t offer any money also restricts artists’ pursuit of livelihoods through art practices over time (Jones, 2017).

- Steep decline in direct funding from ACE for artists’ research and development

Just 135 artists (11.5% of applicants) gained Developing your creative practice awards in 2018 – 19 whereas fifteen years ago, 1,721 artists (52% of applicants) were awarded Grants for the Arts (Jones, 2019). In today’s highly-competitive environment, artists with ‘hidden’ disabilities in particular struggle to formulate acceptable grant applications.

“When you’re writing applications, it seems to me that you have to be able to read between the lines. I’m dyslexic so struggle with words and I’m not good with numbers either. Even the questions in application forms are in a language I just wouldn’t write in and there’s no one to ask for help from.”

In combination, these are policy circumstances which deny all but a very few artists access to levels of financial support that sustain livelihoods through art practices over time. As such, they present a formidable barrier to achieving equality of opportunity and diversity in the arts workforce to which policy aspires (ACE, 2020).

Improving artists’ livelihoods

However there is a logical argument for greater public support to individual artists. As pursuit of art practices is ‘mission-driven’, artists’ modus operandi aligns with the ‘sustainable subsistence model’ of social enterprise (Kerlin, 2013). Artists are thus deserving candidates of public subsidy of some kind to maintain livelihoods through arts practices over a life-cycle. This is because although they employ aspects of entrepreneurial behaviours when delivering value to society with the intention of being financially independent, self-sufficient and sustainable, artists’ ability to benefit economically from the various markets for visual arts the very nature of the infrastructure in which they operate constrains their income-generation (Abu Saifan, 2012).

When arts policies are premised on ‘trickle down’ from funded institutions to artists the detrimental impacts on artists’ livelihoods are inevitable. In such a hierarchy, artists are an ubiquitous human resource positioned at the bottom, to be tapped for others’ benefit. Rather than grounds for co-development, empowerment and transformation, exchanges between artists and arts organisations are predominantly short-term and transactional. The result is that much of what many artists could offer to society is unrecognised.

An alternative to current talent wastage is offered by new analysis drawn from rich, qualitative evidence which identifies three key characteristics that are core to realising livelihoods.

- Confidence to act

Artists acquire confidence to act through access to the tripartite condition of ‘creative space’. This comprises the iterative, slower-paced ‘space and time’ premised on freedom to develop artistically and technically within environments that acknowledge their motivations and beliefs, access to self-determined professional development such as mentoring and the crucial immediate supportive personal and professional ‘circles of trust’ providing consistent emotional, intellectual and artistic sustenance.

- Sense of belonging

Artists’ sense of belonging arises when they have secured ‘situated practices’, those which are conceived, developed and modified by artists over time in relation to artistic ambitions which encompass their personalised circumstances including where they live and their family contexts.

- Ability to ‘get ahead’

Rather than being the subject of gatekeeping, what really sustains the practices of many artists over time are contexts in which they can ‘get ahead’ rather than just ‘get by’ (Putman, 2000). The co-validation arising from self-directed, artist-specific, iterative, negotiated relationships with empathetic and like-minded people and institutions enable artists to consolidate their position on their own terms.

Conditions that foster these characteristics support and amplify ‘motility’, this defined as the volition or ability of artists to move spontaneously and independently in a way strongly reflective of and finely tuned to their specific artistic aspirations and personal needs. Motile artists operate as ‘flesh-and-blood’ people, grounded in their social background and location, whose understanding and framing of their hopes, fears, desires and future development as artists and people is embedded into the experiences, commitments and decision-making of daily lives.

Artists who are motile are less likely to fall victim to systems they have no hand in shaping, including to work environments implicitly and explicitly exploitative of emotional and economic vulnerabilities. As contributors to a cooperative, diverse visual arts ecosystem in which multiple values are co-created, artists with motility have the capacity to sustain art practices and livelihoods over a life cycle.

Thanks to Simon Poulter and Sophie Mellor for an (as yet unrealised) opportunity to present Exploding myths: the future of artists’ livelihoods at CAMP in 2020; ERS (Liverpool John Moores University) for an invitation to present Resetting support to artists at What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About The Artist-Led symposium, 31 January 2020; to Rose Butler, Jon Dovey, Tim Etchells, Adrian Friedli, Simon Poulter, Isabelle Tracy and Hwa Young Jung, my collaborators in two Parallel State: State of the Nation podcasts (on 27 March 2020 and artist Eve Esse for conversations as part of her being writer in residence with CAMP.

References

This text which draws from analysis and commentary from my doctoral thesis Artists’ livelihoods: the artists in arts policy conundrum, 2019 available at http://e‑space.mmu.ac.uk/62635…,

a‑n The Artists Information Company. (2004). Art work: Artist’s jobs and opportunities 1989 – 2003. https://www.a‑n.co.uk/resource/art-work

a‑n The Artists Information Company. (2011) ‘ACE Wednesday’, www.a‑n.co.uk/resource/ace-wednesday

Arts Council England. (2020) Equality, Diversity and the Creative Case: a data report 2018⁄19. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/publication/equality-diversity-and-creative-case-data-report-2018 – 19

Baines, S. and Wheelock, J. (2003b) ‘Creative livelihoods: the economic survival of artists in the North of England.’ Northern Economic Review 33⁄34. pp. 118 – 133

BOP. (2012) The Impact of Creative Partnerships on the Cultural and Creative Economy. London: Creative Partnerships. London: Arts Council England.

Bowness, A. (1989) The Condition of Success: How the Modern Artist Rises to Fame. Text of the Walter Neurath Memorial Lecture, 7 March 1989, Birkbeck College, University of London. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

CCS. (2012) Visual Arts Blueprint. London: Creative and Cultural Skills.

DHA. (2013) Paying artists: Phase 2 findings. Newcastle: a‑n The Artists Information Company.

Ixia (2012) Ixia’s Public Art Survey 2011.

Jones, S. (2017) Artists work in 2016. Research paper. Newcastle: a‑n The Artists Information Company.

Jones, S. (2019) The chance to dream: why fund individual artists? Published on this website.

Kerlin, J. A. (2013) ‘Defining Social Enterprise Across Different Contexts: A Conceptual Framework Based on Institutional Factors.’ Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42(1) pp. 84 – 108.

Louise, D. (2011) Ladders for development: a‑n Research paper. Newcastle: a‑n The Artists Information Company.

Markusen, A. (2013) Artists work Everywhere: Policy Brief. Work and Occupations. 40(4) pp. 481 – 495.

McRobbie, A (2002), Clubs to Companies: Notes on the decline of political culture in speeded up worlds, Cultural Studies, 16(4) pp. 516 – 147.

Putman, R. (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Speight, E. (2015). ‘Listening In Certain Places: Public Art for the Post-Regenerate Age’. In The Everyday Practice of Public Art: Art, Space, and Social Inclusion. Cartiere, C. and Zebracki. M. (eds.) London: Routledge. pp. 177 – 192.

TBR. (2018) Livelihoods of Visual Artists: Summary Report. London: Arts Council England.